Eason Liao *

MASSPHOTON LIMITED Hong Kong, Hong Kong, HK1100, China, eason@massphoton.com

Xiaoxiao Wang

MASSPHOTON LIMITED Hong Kong, Hong Kong, HK1100, China, sunny@massphoton.com

Muhammad Furqan

Chase Farm Hospital National Health Service London, London, United Kingdomm.furqanl@nhs.net

Muhammad Shafa

MASSPHOTON LIMITED Hong Kong, Hong Kong, HK1100, China, shafa@massphoton.com

Shuzhong Li

MASSPHOTON LIMITED Hong Kong, Hong Kong, HK1100,China, szl@massphoton.com

Guangjin Wang

MASSPHOTON LIMITED Hong Kong, Hong Kong, HK1100, China, gjw@massphoton.com

Abstract

LED UV-C LED technology has garnered significant attention as a cutting-edge solution for controlling the spread of infectious and epidemic diseases. This study innovatively integrates UV-C LED technology into an oral disinfector, developing an air disinfection system based on circulating air adsorption. The system effectively captures droplets and aerosols generated during oral diagnosis and treatment, achieving efficient microbial inactivation through an integrated UV-C LED sterilization module. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli and natural environmental bacteria were selected as test subjects to simulate real-world oral treatment scenarios and evaluate sterilization efficiency. Results show that the disinfector achieves a sterilization rate of 97.22% for E. coli and 96.24% for natural bacteria, demonstrating excellent air microbial disinfection efficacy. Additionally, to ensure safe operation, irradiance intensity was measured at three key positions (left, middle, right) around the disinfector, confirming no UV leakage risk during operation. This study represents a systematic exploration of UV-C LED disinfection technology in simulated oral clinical settings, providing critical data support for bioaerosol inactivation and offering theoretical and practical foundations for advancing infection control technologies in oral healthcare environments.

Keywords

UV-C LED, Oral Disinfector, Air Sterilization, Aerosols, Escherichia coli, Prevention

ACM Reference Format:

Eason Liao, Xiaoxiao Wang, Muhammad Furqan, Muhammad Shafa, Shuzhong Li, and Guangjin Wang. 2025. A Study on the Performance

∗Corresponding Author.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the continuous improvement in living standards, health aware-ness, and aesthetic perceptions, there is a growing emphasis on dental aesthetics and oral health, leading to a daily increase in in-dividuals seeking routine oral care and patients presenting with oral diseases. However, the oral diagnosis and treatment process exhibits distinct characteristics compared to the diagnostic quality of other diseases. Instruments such as dental mirrors used by clini-cians during oral examinations, high-speed handpieces frequently employed in dental procedures, and ultrasonic treatment devices generate droplets from patients’ saliva, blood, and other substances during operation. These droplets mix with airborne dust particles to form aerosols that remain suspended in the air [1-3]. Among these, smaller aerosols remain suspended in the air for extended periods before depositing on environmental surfaces or entering the human body via respiration [4, 5]; larger droplets typically follow ballistic trajectories and can still be detected at distances of 2–4 meters from the treatment site [6], though their concentration diminishes with increasing distance from the contamination source [7, 8].Aerosol particles carrying infectious viruses heighten the infection risk for personnel in dental departments.

Currently, air disinfection methods adopted across various hos-pital departments primarily focus on overall upper-layer air pu-rification within the clinic [9]. Existing air purification devices demonstrate effective bactericidal efficacy against certain particles and microorganisms in circulating indoor air [10, 11]. Nevertheless, their performance is limited in specialized settings such as dental clinics, where high-concentration, close-range droplets laden with substantial bacterial loads are generated during treatment. In dental operatory environments characterized by high patient turnover and frequent procedural operations, the proximity between clinicians and patients facilitates rapid dissemination of droplets—propelled by the high-impact forces of therapeutic instruments—into the im-mediate surroundings of dentists and nurses. Conventional air purifiers alone cannot achieve timely and effective removal of air-borne droplets, nor can they enable targeted collection and efficient disinfection of such droplets. Consequently, these approaches fail to fundamentally address droplet transmission during dental pro-cedures, perpetuating elevated infection risks within the clinic and posing significant health threats to clinicians and nursing staff. The development of a dental disinfection device capable of extracting droplet-laden air from above the patient’s oral cavity holds pro-found significance for effectively preventing infections arising from dental treatment processes.

The MASSPHOTON oral disinfector, independently developed and designed by MASSPHOTON, represents the first integration of aerody-namic principles with mercury-free UV-C LED disinfection tech-nology into a single oral disinfection device. The ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (UV-C LEDs) employed in the disinfection process utilize semiconductor chips to convert electrical energy into ultra-violet light, marking an emerging disinfection technology. These chips contain no mercury and generate no harmful gases such as ozone during the conversion process, demonstrating substantial po-tential for replacing traditional chemical methods, mercury lamps, and xenon lamps in the disinfection of air, surfaces, and water [12-16]. UV-C LEDs emit ultraviolet radiation in the 260–280 nm wavelength range, inducing the formation of pyrimidine dimers (particularly thymine/uracil) in DNA and RNA, thereby altering genetic material structure and rendering pathogens incapable of replication [17]. Unlike traditional disinfection methods that treat indoor air as a whole, the MASSPHOTON oral disinfector enables tar-geted and instantaneous removal of droplets at their point of origin. This design effectively prevents droplet dispersion within the clinic, substantially reducing the risk of cross-infection between health-care providers and patients for infectious diseases transmitted via air or blood.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1 Material

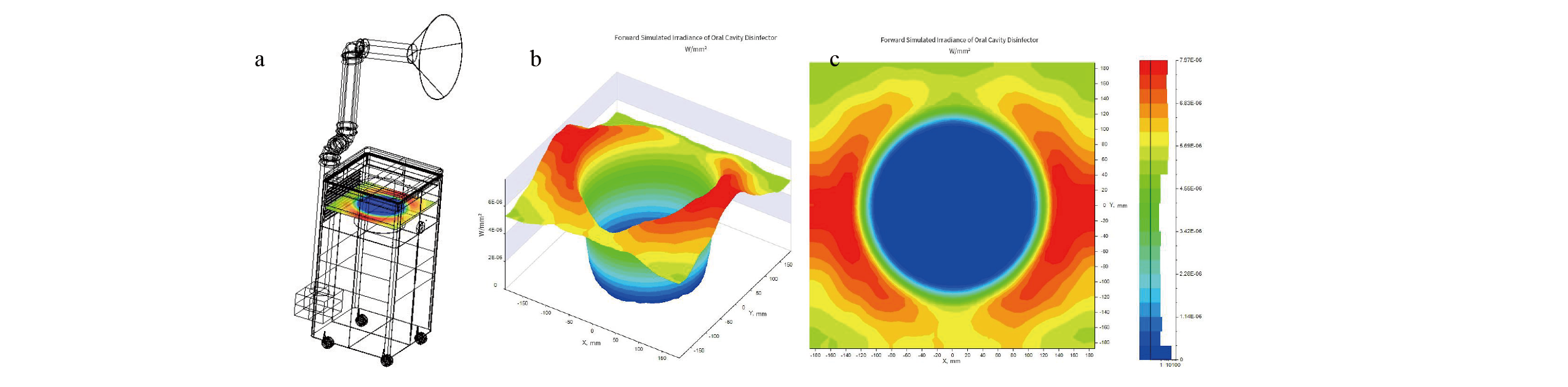

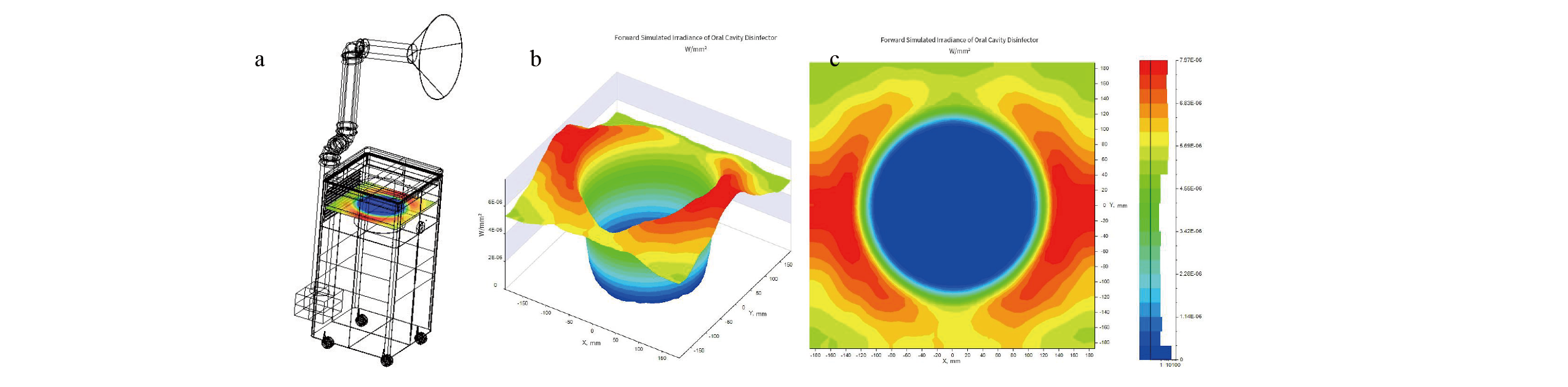

Figure 1. Product diagram and optical simulation of the UV-C LED oral disinfector: (a) 3D view; (b) side view; (c) UV power density distribution.

This study presents the design and optical simulation of an oral disinfector based on UV-C LED technology, as shown in Figure 1. Tailored for dental clinics, the disinfector aims to reduce infection risks for healthcare workers and patients during oral diagnosis and treatment. It employs 275 nm UV-C LEDs and incorporates high-reflectivity materials (>90% reflectivity) at the top to enhance light scattering and minimize UV energy loss. Optical simulations using ray-tracing software indicate that the air filtration duct sur-face receives UV intensity exceeding 794 W/cm2, achieving a 99%sterilization rate for E. coli in 0.36 seconds [18]. The MASSPHOTON oral disinfector is equipped internally with a HEPA high-efficiency filtration structure capable of capturing particulate dust and vari-ous suspended matter ≥0.5 m, thereby providing a compact and energy-efficient solution for infection control in clinical settings.

2.2 Method

The sampling methods and calculation formulas employed in this study were conducted in accordance with Appendix D of GB 28235—Hygienic Requirements for Ultraviolet Disinfecting Devices . This standard, issued by the State Administration for Market Regulation and the Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, constitutes a national standard of the People’s Republic of China, thereby ensuring that the experimental procedures and result calculations are both rigorously professional and scientifically robust.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1 UV Irradiance Intensity

Ultraviolet (UV) irradiance refers to the radiant power of ultraviolet radiation received per unit area, and its magnitude directly deter-mines the efficacy of UV-mediated sterilization. Insufficient UV irradiance may fail to achieve adequate disinfection, whereas ex-cessively high irradiance can result in unnecessary energy wastage. Therefore, establishing the optimal UV irradiance of the device constitutes a primary design priority.

Testing revealed that, following a 5-minute warm-up period, the UV-C LED beads employed within the dental disinfection device ex-hibited irradiance values ranging from 24,368.2 to 27,134.5 W/cm2 when measured at a vertical distance of 2 cm directly below the lamp center using a UV radiometer probe, with an average irra-diance of 25,956.0 W/cm2 (Table 1).These values fully satisfy the UV dose requirements for disinfection in contemporary clinical settings.

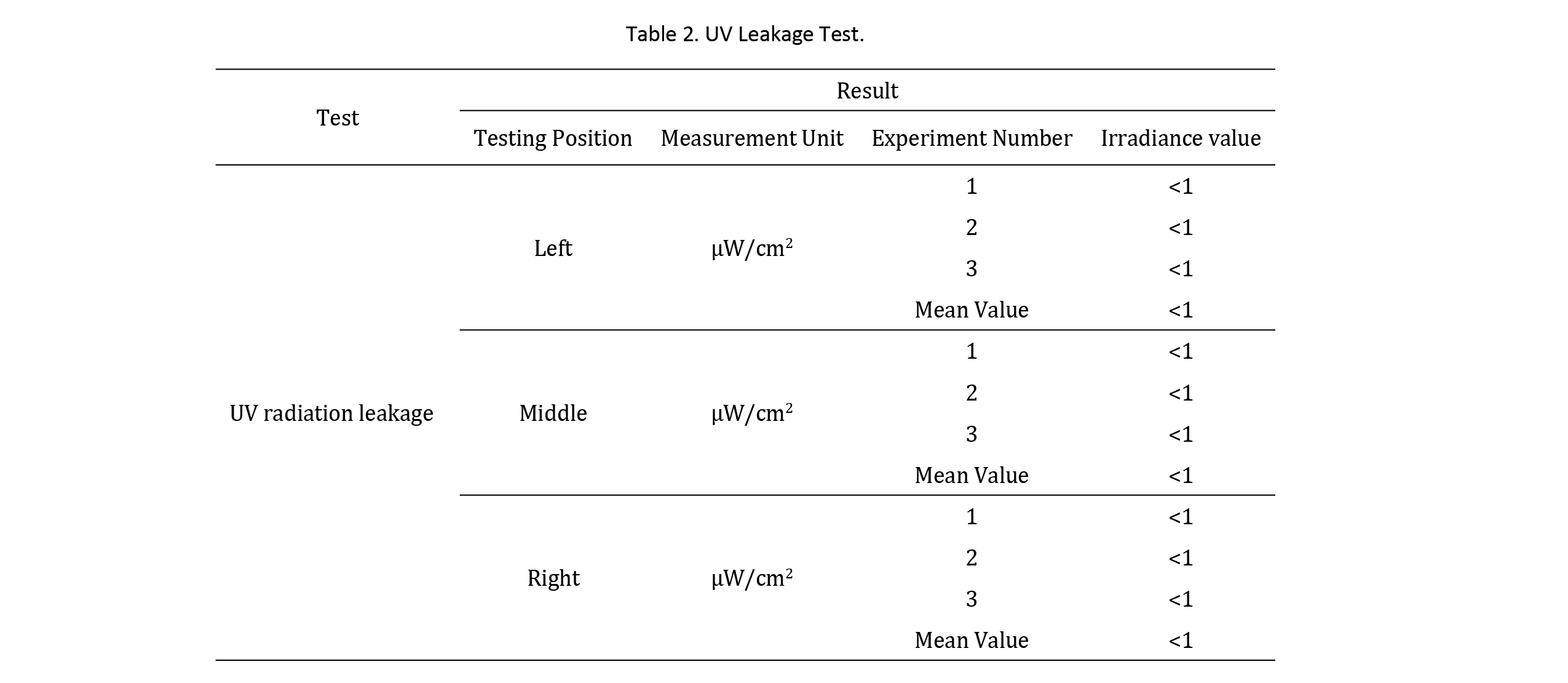

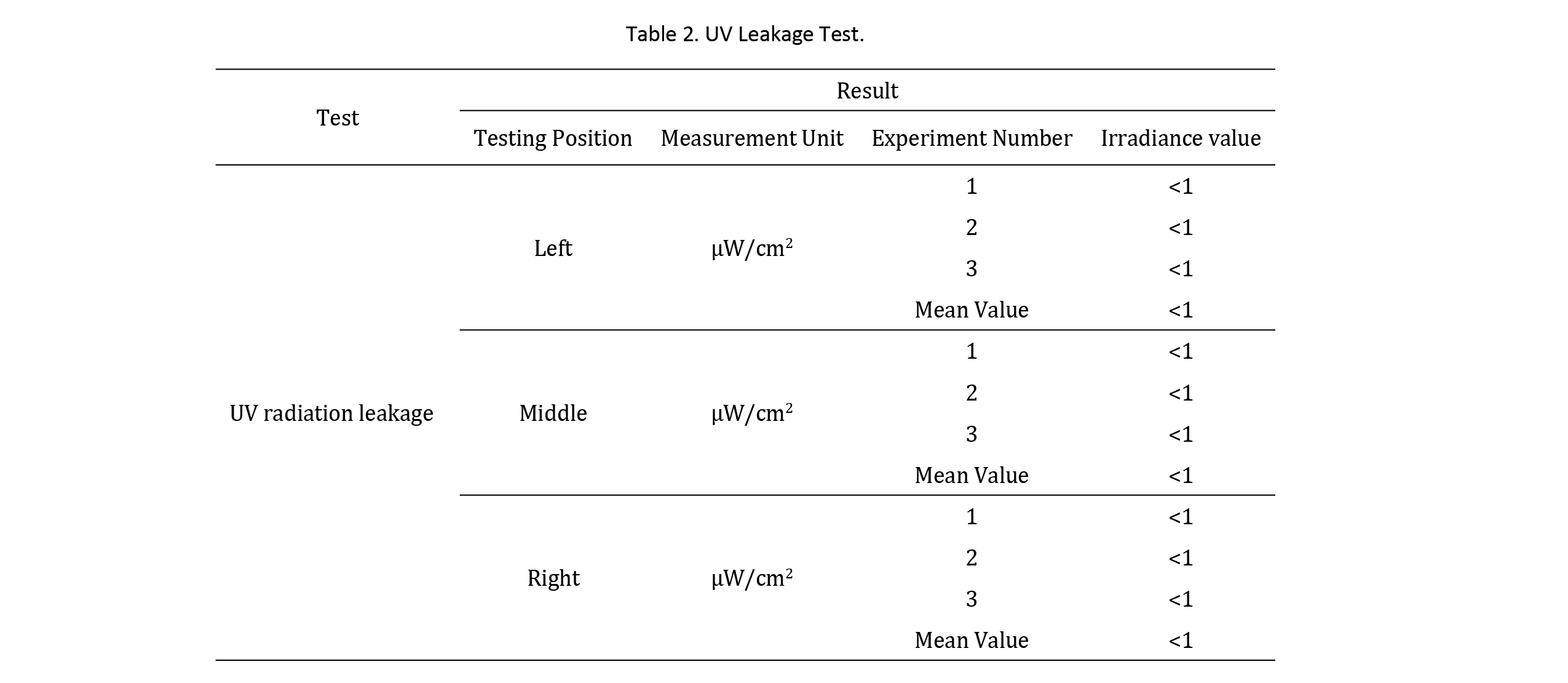

3.2 UV leakage test

Most UV wavelengths are harmful to human tissues, with UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C known to cause varying degrees of skin and eye damage [19-21]. To ensure safety, UV exposure must be minimized or eliminated. Researchers measured UV irradiance at the left, middle, and right diagonal positions around the disinfector, 30 cm vertically from the device, after reaching stable operation. Each measurement was repeated three times for accuracy and reliability.

The experimental results presented in Table 2 demonstrate that ultraviolet (UV) irradiance values measured at the left, central, and right positions along the diagonal perimeter of the dental disin-fection device, at a vertical distance of 30 cm, are all below the safety threshold. These data confirm that UV leakage from the de-vice during operation is significantly lower than established safety limits, posing no risk to human health and enabling genuine human-machine coexistence. This ensures comprehensive safety for clini-cians and patients throughout the treatment process.

3.3 Disinfection Efficacy Testing

During oral treatments, high-speed handpieces generate aerosols from saliva, blood, and other substances, mixing with air droplets and remaining suspended in the clinical environment. To evaluate the disinfector’s efficacy against common environmental microbes, professional microbial sampling and culturing methods were em-ployed. Non-pathogenic E. coli (8099) was used as the test indicator. Before operating the disinfector, an E. coli suspension was sprayed uniformly at the suction vent. To simulate real-world conditions, a handheld sprayer was used at the outlet for intermittent spraying (10 seconds). After stable operation, a six-stage sieve air impactor collected E. coli colony counts at the suction and outlet vents. Sam-ples were incubated upside-down at 36 ± 0.5℃ for 48 hours, followed by colony counting.

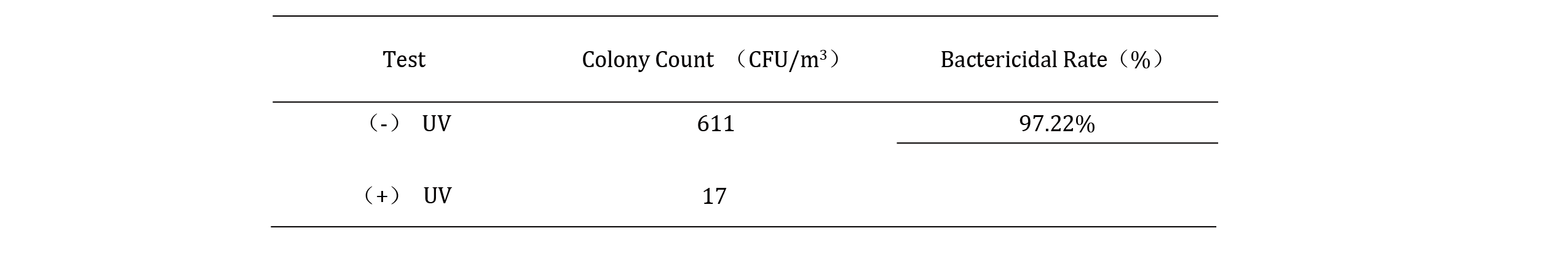

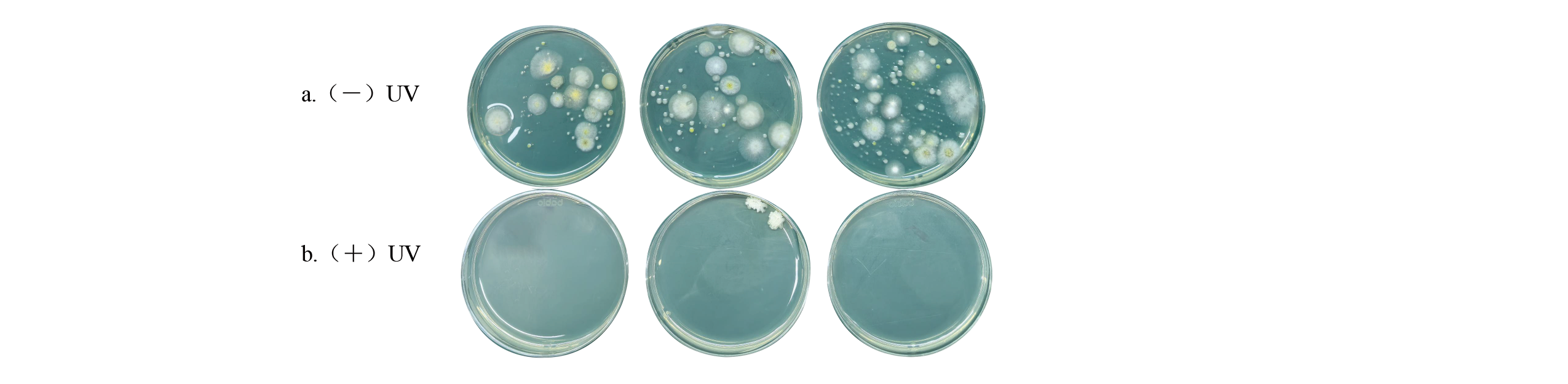

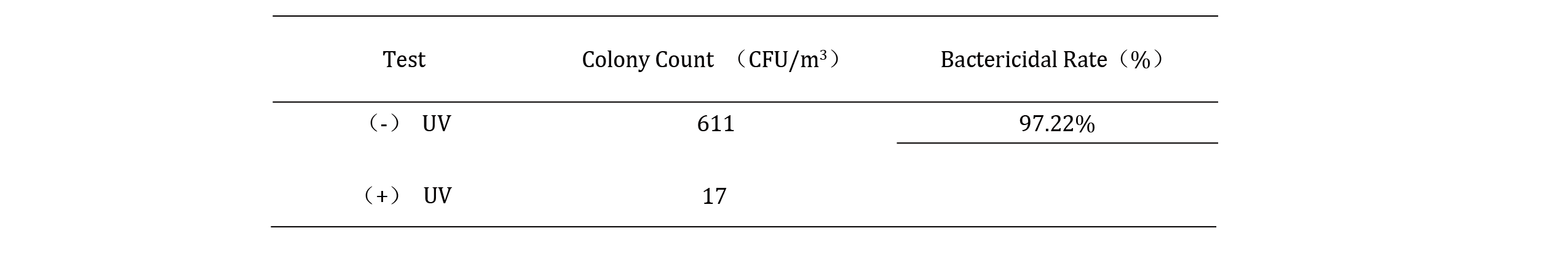

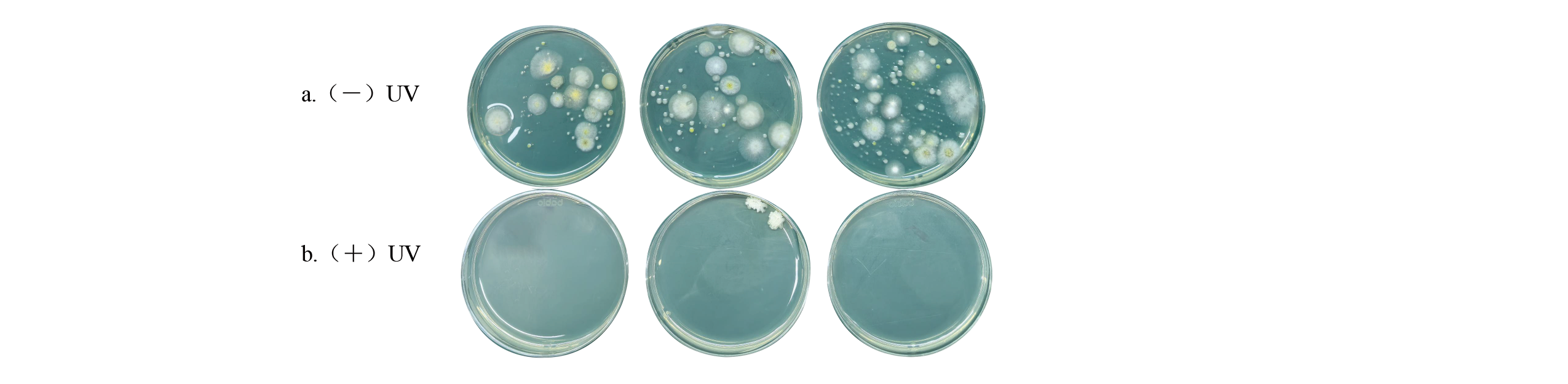

Data from Table 3 indicate that the natural bacterial colony count at the air intake was 611 cfu/m3 (Figure 2a). Following filtration and sterilization by the dental disinfection device, the colony count at the air outlet was significantly reduced to 17 cfu/m3, achieving a sterilization efficiency of 97.2% (Figure 2b). As clearly illustrated in Figure 2, the device’s filtration and disinfection process effectively mitigates infection risks associated with microbial transmission, demonstrating excellent disinfection performance and conferring meaningful functionality in preventing diseases transmitted via aerosols.

Table 3. E. coli Bactericidal Rate Test.

Table 3 shows that the suction vent had 611 CFU/m³ before sterilization (Figure 2a), dropping to 17 CFU/m³ after treatment, yielding a sterilization rate of 97.22% (Figure 2b). Figure 2 visually confirms the disinfector’s ability to significantly reduce microbial transmission risks.

Figure 2. Comparison of E. coli before and after sterilization: (a) E. coli count in air before disinfector operation; (b) E. coli count after disinfector operation.

3.4 Bactericidal efficacy assessment of microbial contamination

Given that the device’s air intake vent faces upward while the ex-haust vent is oriented downward, variations in airflow and the distribution of airborne microorganisms (naturally occurring mi-croorganisms in the air, primarily including bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes) may persist even within the same room. This could potentially influence sterilization efficacy.

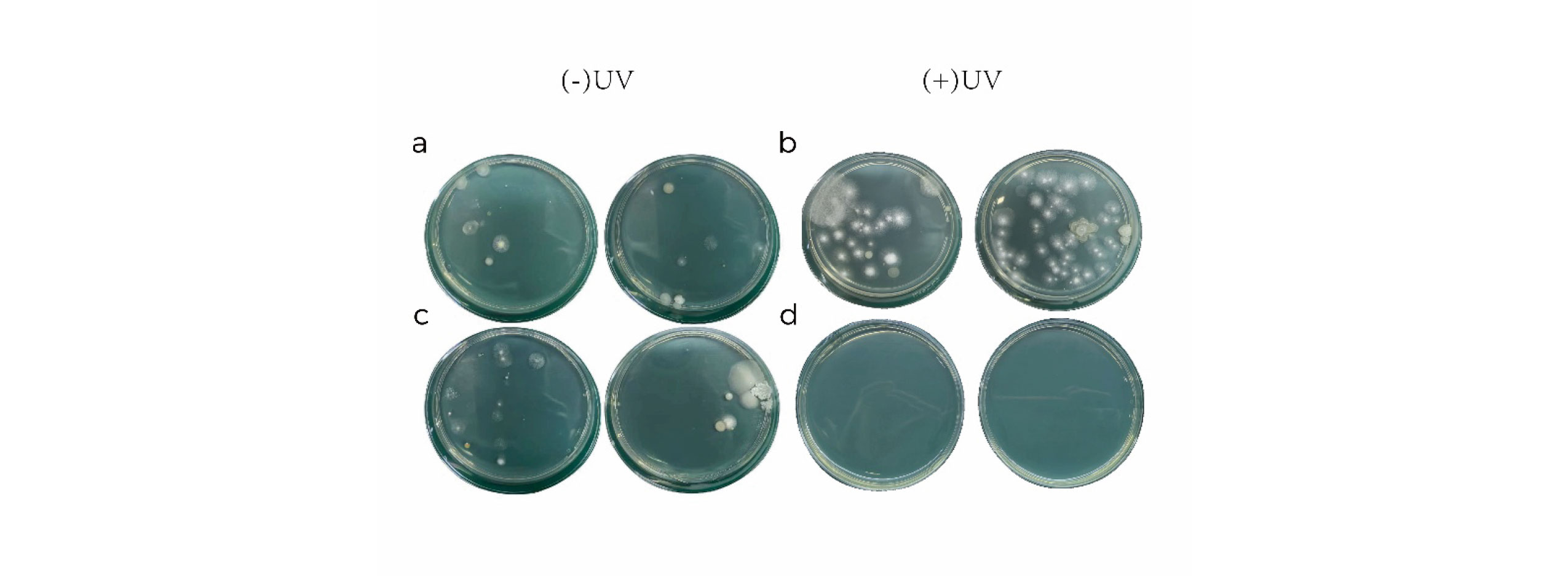

To ensure the experimental results accurately reflect the actual germicidal performance of the oral disinfecting device, researchers collected air samples at both the intake and exhaust vents before and after device activation. The collected petri dishes were incubated in a constant-temperature incubator at 36 ± 0.5℃. After incubation, microbial colony growth on the dishes was observed and quantified.

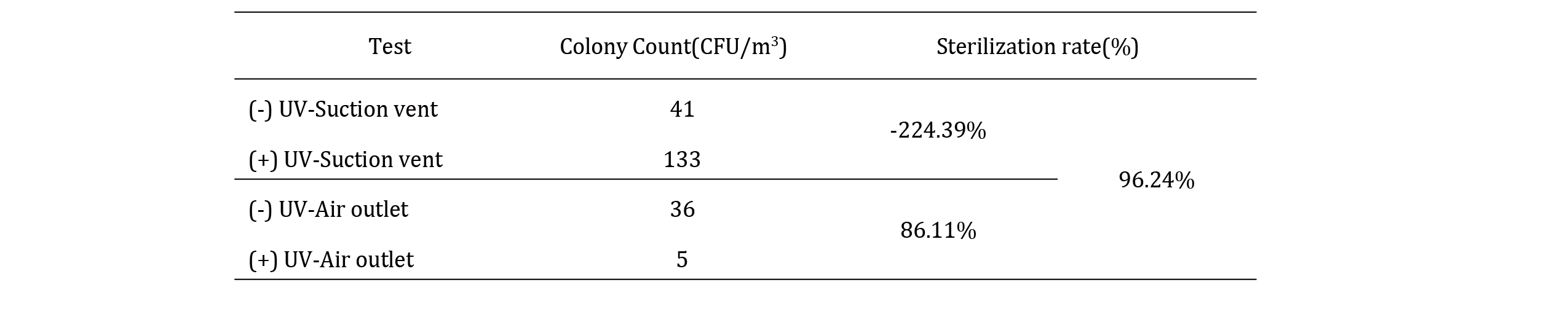

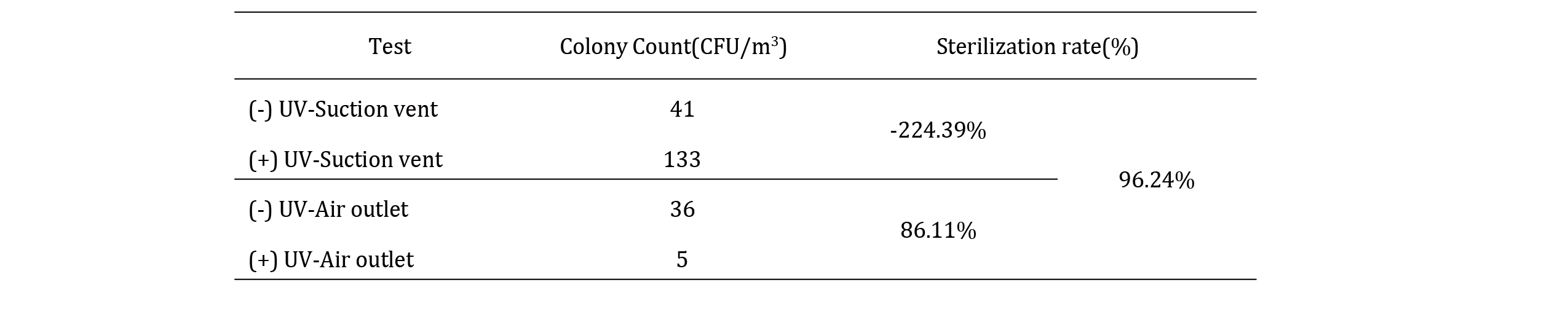

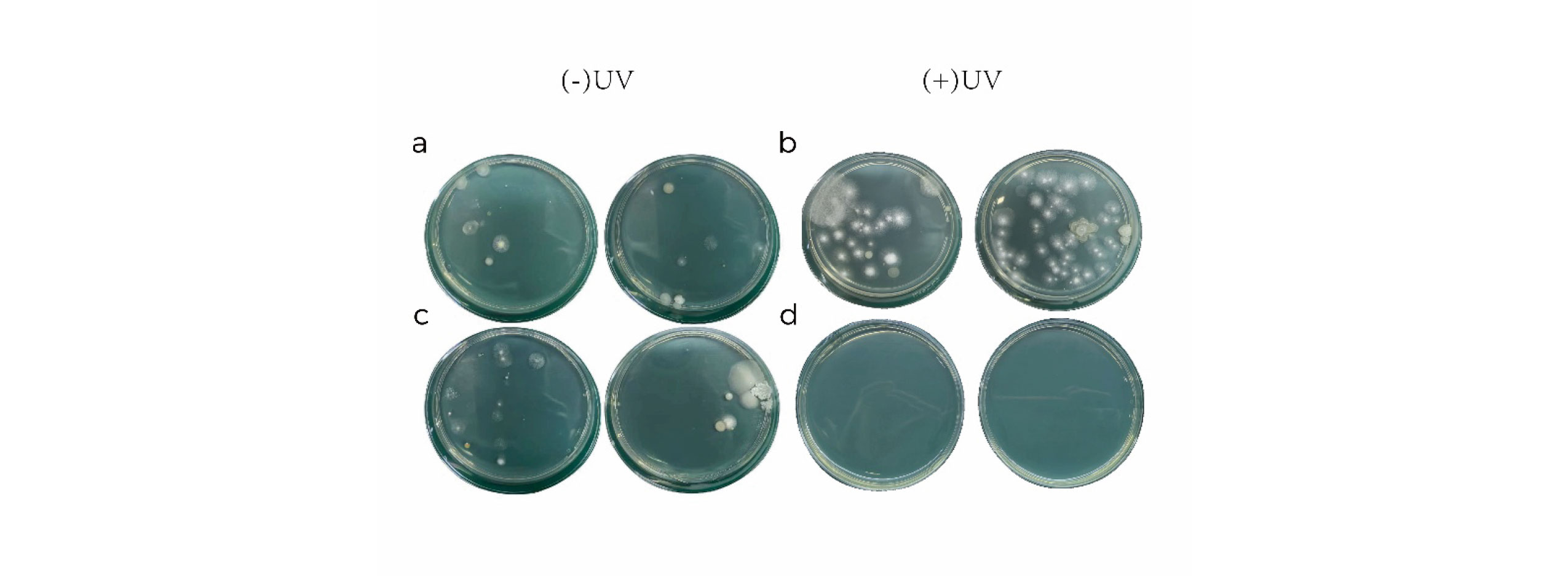

Data from Table 4 reveal that, prior to device operation, the natu-ral bacterial colony count at the air intake was 41 cfu/m3 (Figure 3a). Upon device activation, airflow entrainment rapidly concentrated ambient natural bacteria at the intake, elevating the count to 133 cfu/m3 (Figure 3b)—representing a 224.39% increase over the base-line intake value (41 cfu/m3). Before operation, the outlet colony count was 36 cfu/m3 (Figure 3c), differing by only 5 cfu/m3 from the intake (41 cfu/m3), confirming essentially uniform distribution of natural airborne bacteria. Following activation, high-efficiency filtration and sterilization reduced the outlet count from 36 cfu/m3 to 5 cfu/m3 (Figure 3d)—a decline of 86.11% relative to pre-operation levels. Direct comparison of operational intake (133 cfu/m3) and outlet (5 cfu/m3) values reveals a reduction of 96.24% at the outlet. Figure 3 presents a visual comparison of natural bacterial colony counts before and after passage through the dental disinfection device, clearly demonstrating its superior bactericidal efficacy and capacity to provide a safer and more reliable treatment environment for healthcare providers and patients.

Table 4. Natural Bacteria Sterilization Rate Test

Table 4 indicates that the suction vent had 41 CFU/m³ before operation, increasing to 133 CFU/m³ during operation due to airflow aggregation (224.39% increase). The outlet had 36 CFU/m³ before and 5 CFU/m³ after, a reduction of 86.11%. Comparing suction (133 CFU/m³) to outlet (5 CFU/m³) during operation yields a 96.24%sterilization rate, as visually confirmed in Figure 3

Figure 3. Comparison of natural bacteria before and after sterilization: (a) Natural bacteria count before disinfector operation; (b) Natural bacteria count after disinfector operation.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Hospitals currently exhibit widespread awareness of the risks asso-ciated with airborne disease transmission and actively implement preventive measures. However, effective solutions remain elusive for managing aerosols generated during dental procedures. The MASSPHOTON dental disinfection device innovatively integrates ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (UV-LEDs), high-reflectivity mate-rials, and high-efficiency filtration technologies. UV-LEDs repre-sent an emerging ultraviolet light source, with UV-C LEDs offering distinct advantages over conventional mercury-based UV lamps, including mercury-free composition, no warm-up requirement, extended service life, and compact size [22]. Simulated scenar-ios were employed to evaluate the bactericidal efficacy of UV-C LEDs, with irradiation tests conducted on target microorganisms (Escherichia coli) and naturally occurring environmental bacte-ria. Results demonstrated disinfection rates of 97.22% for E. coli and 96.24% for natural bacteria, indicating robust antimicrobial performance against airborne pathogens. Throughout operation, the device exhibited no UV radiation leakage or ozone generation, thereby ensuring a measurable degree of safety for users. It is noteworthy that the device evaluated in this study has not yet undergone clinical testing in hospital settings.

In the future, the research team will promote the application and validation of this achievement in real-world clinical settings, such as hospital dental departments. This initiative will not only establish a more secure treatment environment for healthcare providers and patients but also provide a more robust scientific foundation for advancements in related fields.

REFERENCES

[1]. Nunayon, S.S., et al., Evaluating the efficacy of a rotating upper-room UVC-LED irradiation device in

inactivating aerosolized Escherichia coli under different disinfection ranges, air mixing, and irradiation conditions. Journal of hazardous materials, 2022. 440(Oct.15): p. 1-12.

[2]. Allison JR, E.D.B.C., The effect of high-speed dental handpiece coolant delivery and design on aerosol and droplet production. J Dent, 2021(112:103746. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103746. Epub 2021 Jul 13. PMID: 34265364.).

[3]. B, P., Aerosol and bioaerosol particles in a dental office. Environ Res, 2014(134:405-9. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.027. Epub 2014 Sep 22. PMID: 25218707.).

[4]. J., S., Dental bioaerosol as an occupational hazard in a dentist's workplace. Ann Agric Environ Med,

2007(14(2):203-7. PMID: 18247451.).

[5]. Peng X, X.X.L.Y., Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci,

2020(12(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. PMID: 32127517; PMCID: PMC7054527.).

[6]. Shahdad S, P.T.H.A., The efficacy of an extraoral scavenging device on reduction of splatter contamination during dental aerosol generating procedures: an exploratory study. Br Dent J. 2020 Sep 11:1 – 10. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2112-7. Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Br Dent J., 2020(doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2288-x. PMID: 32918060; PMCID: PMC7484927.).

[7]. Ionescu AC, C.M.F.J., Topographic aspects of airborne contamination caused by the use of dental handpieces

in the operative environment. J Am Dent Assoc, 2020(151(9):660-667. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.002. Epub 2020 Jul 1. PMID: 32854868; PMCID: PMC7328555.).

[8]. Takanabe Y, M.Y.K.J., Dispersion of Aerosols Generated during Dental Therapy. Int J Environ Res Public Health,

2021(18(21):11279. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111279. PMID: 34769795; PMCID: PMC8583477.).

[9]. Rutala WA, W.D., Disinfection and Sterilization in Health Care Facilities: An Overview and Current Issues.

Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2021(35(3):575-607. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.04.004. PMID: 34362535.).

[10]. Zhang B, L.L.Y.X., Analysis of Air Purification Methods in Operating Rooms of Chinese Hospitals. Biomed Res

Int, 2020(2020:8278943. doi: 10.1155/2020/8278943. PMID: 32076617; PMCID: PMC7016480.).

[11]. Hakim H, G.C.T.L., Effect of a shielded continuous ultraviolet-C air disinfection device on reduction of air and

surface microbial contamination in a pediatric oncology outpatient care unit. Am J Infect Control., 2019(47(10):1248-1254. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.03.026. Epub 2019 May 1. PMID: 31053372.).

[12]. Beck SE, R.H.B.L., Evaluating UVC-LED disinfection performance and investigating potential dual-wavelength synergy. Water Res, 2017(109:207-216. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.11.024. Epub 2016 Nov 7. PMID: 27889622; PMCID: PMC6145099.).

[13]. Zhang H, L.A., Evaluation of Single-Pass Disinfection Performance of Far-UVC Light on Airborne

Microorganisms in Duct Flows. Environ Sci Technol, 2022(56(24):17849-17857. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c04861. Epub 2022 Dec 5. PMID: 36469399.).

[14]. Górny RL, G.M.P.A., Effectiveness of UV-C radiation in inactivation of microorganisms on materials with different surface structures. Ann Agric Environ Med, 2024(31(2):287-293. doi: 10.26444/aaem/189695. Epub 2024 Jun 25. PMID: 38940114.).

[15]. Corson E, P.B.P.A., Hepatitis A virus inactivation in phosphate buffered saline, apple juice and coconut water by 254 nm and 279 nm ultraviolet light systems. Food Microbiol, 2025(129:104756. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2025.104756. Epub 2025 Feb 20. PMID: 40086994).

[16]. Labadie, M., et al., Cell density and extracellular matrix composition mitigate bacterial biofilm sensitivity to

UVC-LED irradiation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2024. 108(1).

[17]. Bhardwaj SK, S.H.D.A., UVC-based photoinactivation as an efficient tool to control the transmission of

coronaviruses. Sci Total Environ, 2021: p. 792:148548.

[18]. Rocha-Melogno L, X.J.D.M., Experimental evaluation of a full-scale in-duct UV germicidal irradiation system

for bioaerosols inactivation. Sci Total Environ, 2024(947:174432. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174432. Epub 2024 Jul 2. PMID: 38960181.).

[19]. Ishida, K., et al., Free-Radical Scavenger NSP-116 Protects the Corneal Epithelium against UV-A and Blue LED Light Exposure. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin, 2021. 44(7): p. 937-946.

[20]. Sathid Aimjongjun, M.S.N.L., Silk lutein extract and its combination with vitamin E reduce UVB-mediated oxidative damage to retinal pigment epithelial cells. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 2013. Pages 34-41(Volume 124).

[21]. DJ, B., Far-UVC Light at 222 nm is Showing Significant Potential to Safely and Efficiently Inactivate Airborne Pathogens in Occupied Indoor Locations. Photochem Photobiol, 2023(99(3):1047-1050. doi: 10.1111/php.13739. Epub 2022 Nov 21. PMID: 36330967.).

[22]. Alonzo A. Gabriel, M.L.P.B., Elimination of Salmonella enterica on common stainless steel food contact surfaces using UV-C and atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Food Control, 2018. 86: p. 90-100.